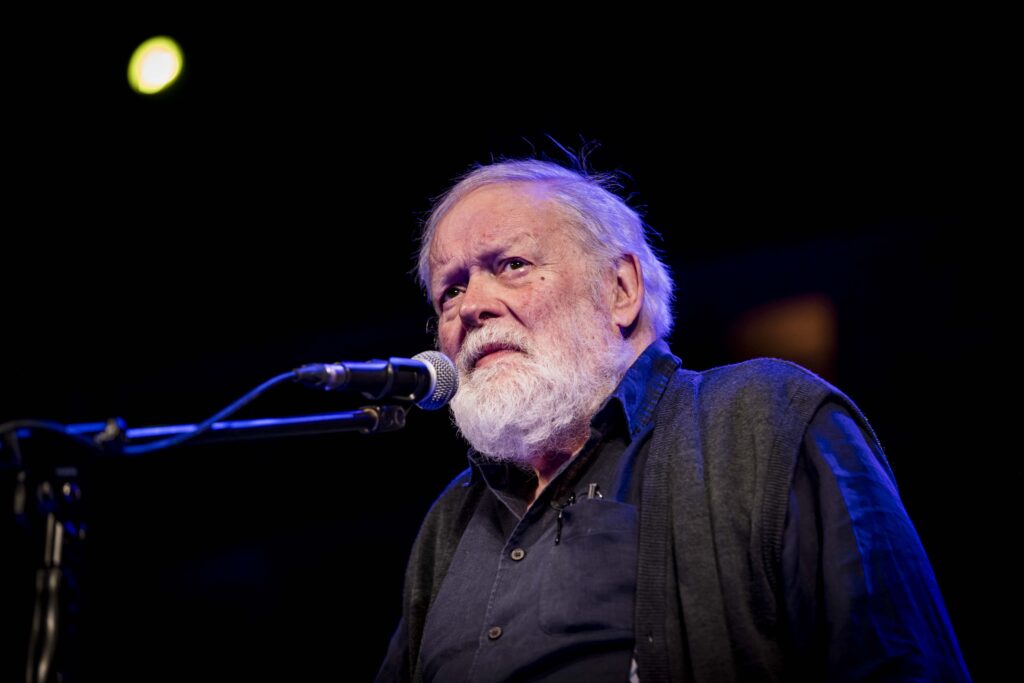

With deep respect and admiration, the Trustees of the Ireland Chair of Poetry would like to share the Eulogy of Professor Michael Longley, whose passing marks the loss of a truly remarkable voice in literature.

Delivered by Professor Fran Brearton at All Souls Church, Belfast, on 1st February 2025, this tribute reflects on Michael Longley’s life and work and his enduring legacy.

Michael Longley: reflections and departures

Fran Brearton

Michael was fond of quoting a comment that John Hewitt once made to him: ‘If you write poetry, it’s your own fault’.

He bequeaths to us a body of work breathtaking in its lyric perfection and its profound humanity. It’s as if his poems have always been here, as naturally formed as the ash keys scattering or the whooper swans flying overhead, so much part of the fabric of our lives it is impossible to remember poetry without him.

Sometimes that work was produced in what he describes as a ‘happy trance…words melting down the page’; but he understood more than most the need to trust silence too – however difficult – as part of the gift. (No point ‘bellyach[ing]’, he said, ‘about “writer’s block” and related ailments’ – the ‘muse’ is not interested.) And, as the holocaust memorials of recent days have reminded us, he knew that poetry, if it is to mean anything, has to be able to face the worst as well as the best of what we, as people, are capable of. The poems are anything but ‘dutiful’; yet they arise out of a deep-seated and complex ethical sense of what the artist’s duty is – all the more deeply felt because of the ‘nightmare happening on [his] home-ground’. ‘I can’t claim’, he wrote in 1969, the year his first book was published, ‘that I…have any longer a life which is my own entirely’; but ‘the imagination has a life of its own, a life that has to be saved; if it isn’t, everything else will be lost’. The need he felt, then and thereafter, to be true to his imagination and to be ‘tuned in’ to the world around him, has enabled everyone else to hear that world’s complicated harmonics a little better.

I first encountered Michael’s work when I was twenty – in an anthology (not an entirely uncontroversial one!) of Contemporary Irish Poetry edited by Paul Muldoon, an undergraduate ‘set text’ that changed the course of my life in ways I couldn’t have anticipated. I went back to remind myself what those first poems were: the beauty and poignancy of ‘Leaving Inishmore’; the early ‘breakthrough’ poem for his father, ‘In Memoriam’, its legacy manifest in the later Troubles elegy ‘Wounds’; the breathless magic of ‘Swans Mating’ – ‘a marriage and a baptism / A holding of breath, nearly a drowning…’; or, from his ‘Wreaths’ sequence, the unflinching poem that metaphorically buries his father ‘once again’ alongside the ‘massacred…ten linen workers’. I loved the strangeness of ‘Second Sight’, with its telescoping of time and place (‘Flanders began at the kitchen window…’) and its ghostly people – including, with his ‘Map of the Underground’, the poet himself. There too is the playful seriousness, the interplay of surface and depth: ‘If I could walk in on my grandmother / She’d see right through me and the hallway / And the miles of cloud and sky to Ireland. / “You have crossed the water to visit me.”’

When I first crossed the water to Belfast, it wasn’t long after the publication of Gorse Fires in 1991, the book whose arrival in print coincided with Michael’s departure from the Arts Council. Many here will remember the excitement generated by that book – his first in 12 years – its perfection born out of trusting silence. Michael’s poetry is animated by both the north and west of Ireland, by the ancient and modern worlds, each irradiating and informing the other across time and space. That his poems are populated by people he loves, admires, and mourns, speaks to an imagination always stimulated by the world around him, and to a generosity of spirit characteristic of the man himself. With poems of transformation and reconciliation, sometimes of anger as well as hope, Michael’s work steered all of us towards the possibility of a different future.

We were, I remember, in the early 1990s, very much in awe of him as one of Irish poetry’s elder statesmen. And that was as it should be. By the time of Gorse Fires, Michael had been writing for thirty years, twenty of them in extraordinarily difficult circumstances, with an accumulation of poems many would be thrilled to call their life’s work. In reality, though, he was only just getting started. When the muse returned at the end of the 1980s, she came back to stay. Gorse Fires is only his fifth published collection of thirteen volumes; a fourteenth book, The Night before Spring – the completion of his life’s work – is still to come.

Twenty years ago, Michael wrote that ‘if poetry is a wheel, then the hub of the wheel is love poetry. Poems that articulate all the other cares and attachments – children, family, friends, heroes, the dead, country, countryside, animals, art – radiate from the hub like spokes in a wheel’. Some of those loves have been spoken of already, including his love for Carrisgkeewaun, the ‘home from home’ that by the time of The Slain Birds has become ‘a state of mind’. But love poetry is ‘at the core of the enterprise’; and love for Edna has always been at the core of his enterprise – a lifetime of deciphering otter prints on the landscape, poem-prints on the page, their love story underpinning everything he writes. In ‘The Pattern’, surely the outstanding love poem of the last half-century, love is the beginning, the ending, and the process of transformation itself: ‘snow has been falling / On this windless day, and I glimpse your wedding dress / And white shoes outside in the transformed garden / where the clothesline and every twig have been covered’.

He also described himself as having been ‘blessed’ by ‘crucial friendships’ that ‘opened my eyes and my ears’. Part of Michael’s being ‘tuned in’ comes from his intense awareness of the work of his poet-friends, the desire, as he says in ‘Letter to Three Irish poets’, ‘to take you all in’. He has been, for many other writers and friends, the ‘hub of the wheel’ himself; the central point – both inspired and inspiring; taking us ‘all in’ in ways that have helped to keep poetry alive.

When the World War I centenary came around a decade ago, a number of poets started reaching for their quills and swagger-sticks; in Michael’s work it was all there already, his ‘haunting’ by the boy soldiers of the First World War, including his own teenage father, present in every book he has written – a preoccupation which has taken him outwards into writing of some of the worst atrocity and suffering of the 20th and 21st centuries. More recently, as we’ve all woken up to anxieties about the environment, about the need for ‘eco-poetry’, it turns out he was always writing this too. Longley’s poetry is a ‘Song of the Earth’ – often celebratory, always cautionary, and in its deepest sense political. With every line that embraces birds, flowers, and animals comes a profound sense of the landscape under threat, a landscape he has recorded even as some of it has changed irrevocably or disappeared.

Michael Longley is, following Yeats, the great self-elegist of the last half century, who has been counting the years along with the whooper swans, the otters, and the wild flowers. To read his work is to know that what we have is precious but that it may be provisional too, held for us only by and in the form and shape of the poems: Odysseus ‘cradled like driftwood the bones of his dwindling father’; in ‘The Ghost Orchid’, ‘Just touching the petals bruises them into darkness’; the otter ‘Tying and untying knots in the undertow…engraves its own reflection and departure’. And Michael, faithful friend, infallible guide, has done everything he can to prepare us for this moment too.

He didn’t much like enormous tomes, weighty 1000-page ‘Collected Poems’. His last gift to us before his death is the self-selected distillation of more than 60 years of poems into a new volume, Ash Keys, which marked his 85th birthday. It opens with his 1963 love poem for Edna, ‘Epithalamion’; it closes with ‘Totem’ from The Slain Birds, in which ‘all the creatures’ – the ‘tawny owl, the ‘sleepy…badger’, otters, donkeys, hares and stoats – are imaginatively recreated in ‘a ghost dance’ with his twin, his father, his mother, the poets who have gone before him.

The poem ‘Ash Keys’ itself (from The Echo Gate) isn’t as well known, perhaps, as some of the later and oft-cited works by Michael which have made their occasion in public; but for a poet always reminding us to look for what we might have missed, that is at least one reason to end with some lines from its closing stanzas:

Far from the perimeter

Of watercress and berries,

[…]

… the ash keys scatter

And the gates creak open…